California schools lose tree canopy, Ossola team finds

Meanwhile, temps on sunny playgrounds hit up to 120 degrees

Researchers from the UC Davis Department of Plant Sciences spent their summer at elementary schools across California, measuring tree canopies and just how hot playgrounds, basketball courts, soccer fields and other outdoor spaces can get.

Tree canopies at schools here cover only about 4 to 6 percent of the average campus. This means the state's roughly 5.8 million students at K-12 public schools often spend recess and other outside activities under the glaring sun.

As part of their work, scientists mapped tree cover and heat over the course of a hot day at schools in inland and coastal areas of Northern and Southern California.

“We are trying to measure to what extent we are exposing kids to temperatures that might be stressing their body to a level that becomes uncomfortable or dangerous,” said Alessandro Ossola, an associate professor in the department who directs the UC Davis Urban Science Lab.

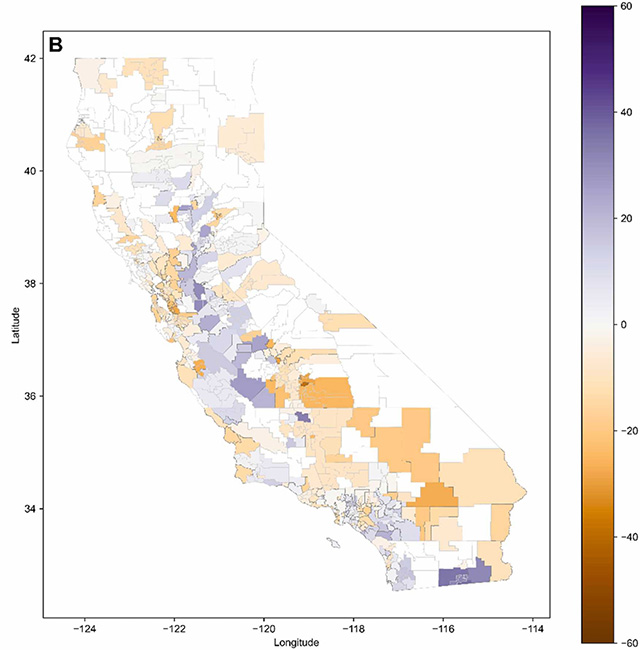

It’s especially timely. A recent analysis by Urban Science Lab members found 85 percent of schools lost trees between 2018 and 2022. While the average decline was less than 2 percent, some districts in the Central Valley lost up to a quarter of their tree cover, according to a paper published this month in the journal Urban Forestry and Urban Greening.

The findings are troubling, as climate change will likely intensify extreme heat and drought, underscoring the urgency of improving tree canopy cover, according to the paper.

“How can we use trees and nature-based solutions to help schools and districts adapt to that future?” Ossola pondered.

Funding for the research came, in part, from the United States Forest Service, the U.S. Department of Agriculture's National Institute of Food and Agriculture, the federally supported Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research and the German Research Foundation. The nonprofit Green Schoolyards America also contributed through its California Schoolyard Tree Canopy study.

Ossola's team included Luisa Velásquez Camacho, Moreen Willaredt and Pooja Singh, all in the Department of Plant Sciences.

Measuring the heat

Equipped with mobile weather stations, a roving and sensor-laden cart named MaRTyna and sensors measuring wind speed, wind direction, temperature, radiation and other data, the teams recorded heat levels on various surfaces, from wet green grass and shaded areas to dead sod and dark rubber.

At one California school in San Bernardino County, the team measured a heat index – or feels like temperature – of 120 degrees in the late afternoon in several areas.

“That’s very extreme heat exposure,” said Luisa Velásquez Camacho, a first year postdoctoral scholar in the Urban Science Lab. “Kids don’t know how to regulate. They don’t know if it’s too hot for them. They just want to be out and playing.”

A collaborative approach

UC Davis researchers collaborated with scientists from UC Berkeley, UCLA and the U.S. Forest Service.

“Most schools are actually a nature desert, which is antithetical because we know that early life exposure of humans to nature is critical for them to develop skills, improve their microbiome, become more environmentally active and so on,” Ossola said. “Trees are a hidden asset and an underutilized asset.”

At each of the schools, the team sought to measure the heat exposome, which is the heat and radiation coming from the sun and reflected by buildings and surfaces.

“We’re trying to cover all the radiation coming from all different directions,” Ossola said.

They deployed up to 20 weather stations around the perimeter to measure air temperature and relative humidity. Another 20 tripods topped with sensors set at nearly 28 inches tall – the typical height of a young student – were placed throughout the property on asphalt, grass and open spaces to measure temperature, the heat index, wind speed, wind direction and other information.

“You can see the differences between surfaces,” Velásquez Camacho said. “The worst is rubber. At some of the schools, the rubber was new and the smell was everywhere.”

Technology and trees

MaRTyna – the capital letters stand for Mean Radiant Temperature – is based on a roving sensor designed at the University of Arizona. It records measurements every five seconds, collecting information related to mean radiant temperature and other data points.

Three time each day, the team “walked” MaRTyna around the entirety of school grounds to measure different microclimates. Each trip took one hour and Ossola estimated the team walked 25,000 steps at each site and nearly 280 miles over the course of the summer.

“We’re measuring how heat evolves over time,” Ossola said.

The UC Davis, UC Berkeley and UCLA teams also took tree inventories at schools in the Bay Area, Los Angeles basin and the greater Sacramento area.

“Some were super-well-planted and really green,” said Alden Hughes, a senior environmental science and management major. “Others had less that 50 trees and felt noticeably warmer.”

Students in the Environmental Policy and Management graduate group have been working on a parallel investigation to understand how local policies affect the planting and removal of trees on school campuses.

For Kaylianne Jordan, a senior in viticulture and enology who is interested in sustainability, the summer research helped her better understand trees, their health and effects on an area.

“Knowing the value of having a lot of trees is something I’ve really learned this summer,” Jordan said. “The shade from trees is different than the shade from buildings. Trees mitigate more heat.”

The team worked in the summer, which could represent June or earlier months by the end of the century as the climate grows warmer. They found that temperatures peak along the coastal areas early during the day, compared to inland locations such as the Central Valley and San Bernadino Valley, where heat builds up for longer.

Media Resources

- Alessandro Ossola, Department of Plant Sciences, aossola@ucdavis.edu

- Luisa Velásquez Camacho, Department of Plant Sciences, lfvelasquez@ucdavis.edu

- Emily C. Dooley, College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, ecdooley@ucdavis.edu