Pressure Bombs Help with Crucial Tree Nut Watering Decisions

A device whose concept was born in the 1960s has become a key part of the water-saving toolbox for many California tree nut growers.

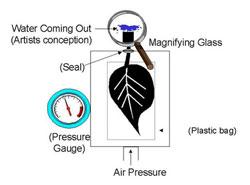

The pressure bomb, or pressure chamber, has advanced in sophistication over the years, but its purpose is essentially the same: to tell a grower whether a tree is stressed by too little, or too much, water.

University of California farm advisors who’ve been promoting the device in recent years say it’s essentially a blood pressure test for tree leaves. By testing a leaf with the device, a grower can see how well a tree is pulling water up from the soil, and can plan to provide irrigation when the tree really needs it.

The device has also helped with research. Ken Shackel, UC Davis plant scientist and professor, says the pressure bomb and other monitoring devices most recently helped researchers determine that it’s better to hold back on irrigating walnut trees in the spring rather than in the summer.

“We would not have discovered this if we hadn’t had the technology to monitor stress,” he told growers during a field day in an orchard near Red Bluff, Calif.

Ken Shackel, University of California, Davis, plant scientist, discusses pressure bombs during an irrigation field day in a walnut orchard near Red Bluff, Calif. (photo: Western Farm Press)

Why a Pressure Bomb?

Lots of people have asked him why the device is called a pressure bomb, Shackel says. The earliest versions of the device looked like a bomb calorimeter, he explains, and it uses compressed gas, which could explode.

There are some differences between testing tree stress with pressure bombs and measuring human blood pressure, he says. While most people take their blood pressure while at rest, the only time trees are at rest is at night, and that doesn’t tell how well the tree is pulling water into leaves during the heat of the day.

Leaves for the tests are typically taken from the base of the tree near the center, Shackel says, even though there’s more suction the higher one goes up the tree. “When a tree is under water stress, the whole tree is under stress — not just leaves at the top.”

He and other UC Davis scientists have been using pressure bombs to measure plant water stress since the early 1990s, but the devices became popular with growers and UC Cooperative Extension (UCCE) advisors at the height of the historic drought in 2012–2016, when shortages led to drastic surface water cutbacks. The UC Davis Fruit and Nut Research and Information Center launched a website in 2014 to help growers interpret readings from their pressure bombs.

While the pressure bomb used to be the only available technology that could help a grower monitor the effects of deficit irrigation, today there are other tools to aid in watering decisions. Many were showcased during the field day, which was cosponsored by UCCE, USDA, and North Valley Ag Services.

Other Devices

Among them were dendrometers, which can measure very small expansions and contractions of tree trunks to give users information about water stress; a leaf-monitoring system recently designed by UC Davis professor and biological and agricultural engineer Shrini Upadhyaya that measures leaf temperature, wind speed, humidity, and other factors that may affect a plant’s water needs; and a drone that can be flown over orchards to measure factors such as uniformity and heat stress.

Still, thousands of hours of work have been put into perfecting pressure chambers, says Jeff Hamel of Albany, Ore.-based Plant Moisture Stress Instruments. And growers continue to perfect ways of using them.

Ryan Kaplan, an Orland walnut and pistachio grower, developed a mobile device app to collate pressure chamber data that can get a little overwhelming, he says. He developed the Pressure Bomb Express app with the help of interns from California State University Chico.

“You start pressure bombing, input the numbers, and at the end of the day you hit ‘upload’, and have a report sent to your computer,” says Kaplan, who gave a presentation at the irrigation field day. “It instantly makes the data you collect a real-time information tool.”

(Article by Tim Hearden, Western Farm Press, June 2018)