Sad-looking Herbarium specimen yields clues to wine country blight

Bacterium causing Pierce's disease found in century-old grapevine

In 1906, a field scientist named Alfred Tournier acquired scraggly branches from some sorry-looking grapevines in Modesto, in California’s Central Valley. Most of the leaves had dried up and fallen off. Even the branches had shriveled.

Bits of the dying vine were pressed, dried and stored in a collection of grapevine specimens at the University of California, Berkeley. It was an example of what then was called California vine disease or Anaheim disease, for the place where the malady was first recorded in the 1880s. The blight had been striking vineyards throughout the state, threatening to destroy the grape industry. It would be a century before scientists could identify its cause.

Fast forward to 2022: Tournier’s grapevine sample was now in a cabinet in the collections room at the UC Davis Center for Plant Diversity Herbarium. It stirred much excitement when a team of scientists from CIRAD -- France’s version of the United States Department of Agriculture -- arrived. They had come to investigate potential sources of the blight, which was expanding in France due to climate warming.

Pierce’s disease is the malady’s modern name. It is triggered by the bacterium Xylella fastidiosa, which clogs the tiny tubes called xylem that transport water and nutrients throughout the plant. Starved of nourishment, the vine’s grapes shrivel, its leaves turn brown and drop, and eventually the plant dies. A study estimates the disease still costs California growers and taxpayers more than $100 million a year in lost revenue and prevention efforts.

Pierce’s disease has spread to France, Portugal, Spain, Italy, Israel, even Taiwan. The bacterium is now known to infect hundreds of species of plants, causing disease in citrus, stone fruits, coffee, olives, alfalfa, blueberries and pecans. The visiting CIRAD scientists sought to discover where the bacterium had come from, so they could better understand the causes and sources of modern X. fastidiosa outbreaks.

In a new study released this week by the journal Current Biology, the CIRAD researchers and colleagues from UC Berkeley described the surprising journey of X. fastidiosa, using genetics to recreate its roadmap.

Tournier’s vine sheds light on global plant diseases

From Tournier’s specimen at the Herbarium, the French team isolated and reconstructed a nearly 120-year-old genome of the bacterium and compared it to 330 contemporary strains. This genome provides a new historical perspective on when the pathogen arrived in California and its early spread.

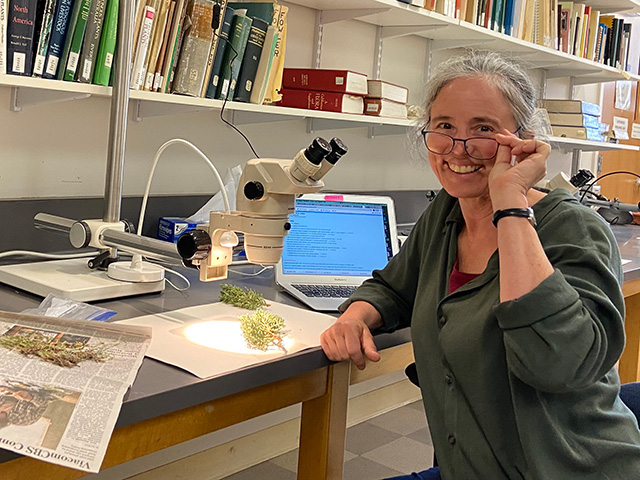

“The CIRAD team was our first set of post-pandemic researchers in early 2022. They spent several days here and at the UC Berkeley herbarium, removing small pieces of tissue from grapevine specimens and other plants suspected of hosting Xylella fastidiosa,” said Alison Colwell, the Herbarium's curator. “They knew in advance from our online specimen data that UC Davis houses a large collection of historic California Vitis, but they were surprised to see how extensive our collection is.

“When we found two specimens from 1900 and 1905 marked ‘Anaheim disease,’ there were gleeful cries of ‘mon Dieu!’”

Scientists had long assumed that X. fastidiosa was first introduced to California in the 1880s or slightly before, when many species of grapes were brought to the state from the East to establish vineyards. At the time, local newspapers such as the Pacific Rural Press started reporting a mysterious new disease that was affecting “a large number of vineyards” in Anaheim and the Santa Ana Valley.

However, the genomic data suggest the pathogen actually arrived in the U.S. nearly 150 years earlier, around 1740, and came from Central America. The data further suggest the disease in California arose from, not one, but at least three separate introductions of the bacterium.

That makes Tournier’s sorry grapevine important for understanding the global spread of plant diseases today, the researchers said.

The fact that there were likely three separate introductions of X. fastidiosa also suggests that multiple, genetically distinct populations of the pathogen may exist in California. Like different variants of SARS-CoV-2, these populations may all cause similar symptoms, but they can respond differently to stressors such as climate change.

And as with the virus that causes COVID-19, those biological differences may be small, but they can be important for guiding disease management, the researchers argued.

Herbaria: A treasure trove for science

The UC Davis Herbarium houses about 300,000 plant specimens collected from all over the world, the greater half from California -- both native and agricultural specimens. The collection is primarily used for research on California flora such as weeds and native plants, describing new species, documenting the features of plant groups and teaching plant identification.

However, as the collection is digitized and becomes searchable online through the Consortium of California Herbaria web portal, researchers from all over the world are able to find these collections and come to study them, Colwell said.

“Our herbarium collections are basically pieces of dried plants stored in paper, a method of preservation developed in the 15th century, on the heels of the industrialization of paper production,” Colwell explained. “It’s a simple preservation method, but time has proven it’s effective. Modern technology -- especially DNA studies and the internet -- has made collections like ours even more useful for many more fields of inquiry and accessible to many more researchers.”

Tournier's vine is among 1,100 Vitis specimens collected from California agricultural experiment stations between 1895 and 1910, Colwell said.

The CIRAD researchers -- Adrien Rieux, Nathalie Becker and Paola Campos of France's Agricultural Research Center for International Development -- tested 10 sickly-looking grapevine specimens from the collection. From those, only Tournier's sad branch tested positive for X. fastidiosa. The scientists also tested specimens from UC Berkeley’s University and Jepson Herbaria, but none tested positive.

“A grapevine with a lot of X. fastidiosa is not necessarily a prime candidate for an herbarium collection, so we were very lucky to find even one infected sample,” said Monica Donegan, a graduate student at UC Berkeley and co-first author of the study.

Becker and Rieux led the painstaking work of isolating the old and degraded X. fastidiosa DNA from the specimen. Even if the bacteria on the specimen are dead, scientists can still isolate and sequence the nucleic acids that code for the genes.

With the genome sequence in hand, the researchers then used bioinformatics software to compare the genes from the century-old X. fastidiosa to contemporary strains. This analysis provided an estimate of how quickly the pathogen’s DNA mutates over time, which, in turn, allowed them to estimate the timing of key moments in the bacterium’s evolutionary tree.

-- Alison Colwell contributed to this story.

Media Resources

- Trina Kleist, UC Davis Department of Plant Sciences, tkleist@ucdavis.edu, (530) 754-6148 or (530) 601-6846

- Kara Manke is a writer for UC Berkeley News.

- For a contemporary account of Pierce's disease in California in the early 20th century, see Hussman, 1910, Grape investigations in vinifera regions. USDA Bulletin 172.