Proper Phosphorus Levels Keep Rice Growing Well

Rice nutrition, salinity, and water management were all on Bruce Linquist's mind as he addressed attendees at a recent field day in Glenn County.

Management of water levels and nutrient requirements of a growing rice crop can spell the difference between bountiful yields of high quality rice and a crop that is deficient in both yield and quality. (photo: Steve Adler)

Deciding the right amount of phosphorus to apply and how to apply is important, said Linquist, who is assistant Cooperative Extension specialist and faculty member in the Department of Plant Sciences at the University of California, Davis.

"The big question in terms of phosphorus is whether you should apply it. In some cases you don't," Linquist said, adding phosphorus deficiencies are not that common here, but growers do need to keep on applying it; otherwise, it may become depleted.

"How do you determine if you need to apply? You can do it in different ways," he said, including soil and plant tissue testing.

Linquist advised growers that if they are sending soils to the lab, to make sure that the lab is doing the Olsen-P test.

"Sometimes they're doing the Bray, and that does not really work very well for flooded, anoxic soils," Linquist said.

A plant test is another option, but Linquist said he doesn't like those as well, because the information is probably going to be too late to make a phosphorus fertilizer application.

"You really need to apply your phosphorus fertilizer, if you have a deficiency, before 30 days. If you apply it after that, it's not going to be that effective," he said.

Linquist suggested a third option -- growers use the phosphorus fertilizer input/output budget to determine phosphorus needs.

A website (http://agric.ucdavis.edu) was launched this year by the agronomy research and information center that covers several different crops, including rice. There are areas for news, blogs, presentations, reports, contacts, and there is also a phosphorus fertilizer budget and application online calculator, Linquist said.

Growers can enter in the information on the website, and it will calculate and tell a grower whether he needs to increase or decrease phosphorus applications, Linquist said, adding that very little phosphorus is lost through water.

"It's absorbed very strongly to soils, and therefore we also have very little leaching. So what you apply tends to stay there," Linquist said.

Many growers retain the straw, and by doing this, they can calculate a phosphorus budget, he said.

Linquist suggested looking at a five-year average of inputs minus outputs how much grain and straw was removed. Many growers may have low soil phosphorus, but they have very high yields, he said.

"They are often getting 90 to 100 sacks," Linquist said, "but they're only putting on 40 units of phosphorus and that's 10 units too little.

"If you're getting 100 sacks, and you're adding 40 units, you're depleting your soil every year by 12 units of phosphorus. To maintain it, you need to be applying about 50 units," he said.

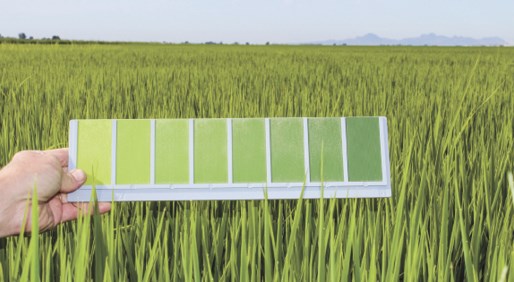

This leaf color chart, developed by UC Cooperative Extension farm advisor Cass Mutters, helps rice growers determine whether to apply nitrogen to their crop. (photo: Kathy Coatney)

There are more top-dress nitrogen applications going on now than there have been for a while, but there's no benefit to splitting that nitrogen between a preplant and top-dress, Linquist said.

"Put it on all the way at the front. It's cheaper," he said.

There are exceptions to this, and there are some reasons to top-dress, Linquist continued:

- If there were nitrogen losses early on.

- The field dried out, resulting in de-nitrification losses.

- High yield potential may require more nitrogen.

The leaf color chart and SPAD meter are also tools growers can use to determine nitrogen needs, he said.

Linquist has also done quite a bit of work on water budgets in rice fields, and he said there are some things that relatively little can be done about.

"We're not going to be able to change our evapotranspiration. That's a fairly solid number," he said, adding it's also difficult to do much about percolation and seepage.

"What we can do a lot about, what guys have been doing, is reducing the amount of spill coming off the end of the field, and that's a fairly high number," he said, adding the research found that could be reduced to zero.

A lot of irrigation districts didn't allow growers to have any spill, and no spill helps minimize salinity, Linquist said.

"Having water constantly flowing through prevents salinity buildup. Also, maybe where salinity isn't an issue, by allowing continuous flow, makes it easier to maintain water levels," he said.

Linquist said that over the past two years, he found that with an open field, there is a lot of standing water that doesn't have canopy coverage yet. The water gets very hot, which causes a lot of evaporation, and tends to build up salts, he said.

"As you get to the latter part of the season, you have canopy coverage, and the water has cooled, and so you're not getting a lot of evaporation, but you're getting a lot of transpiration," Linquist said, adding the floodwater remains relatively cool.

"So your real problem times are in this period early in the season," he said. "These fields that we looked at were fairly uniform fields. They didn't have the alkali patches sitting in them, and they were pretty much uniform with respect to soil.

"I was amazed looking early on that it was very difficult to see the effect of salinity throughout much of the crop cycle, even when we had imposed some very high salinity levels," he said.

Linquist said he saw symptoms of salinity where there were really high levels.

"At the grain development, you see these undeveloped grains. They come out just very feathery white where there should be a grain, and we tend to see that on some very high salinity areas," he said.

Draining early to save some water is a good practice, Linquist said, but that salinity tended to dry the plants out quickly.

"Based on what I saw, I would tend to hold my water just a little longer if I had high salinity. Let that grain and those leaves be a little more productive for a little while longer," he said.